Pooja Rangan, Akshya Saxena, Ragini Tharoor Srinivasan, Pavitra Sundar

In 2021, as our co-edited book Thinking with an Accent entered production, a Silicon Valley start-up began advertising an app that uses AI to modify accents in real time. As one reporter put it, “rather than learning to pronounce words differently, technology could do that for you. There’d no longer be a need for costly or time-consuming accent reduction training. And understanding would be nearly instantaneous.” Thinking with an Accent offers a sorely-needed alternative to this vision of a world where communication and understanding happen automatically, and seemingly magically, without translation or friction. Taking as our point of departure the idea that an accent is not an unfortunate thing that only some people “have,” but rather a powerful and world-forming mode of perception, a form of minoritarian expertise, and a complex formation of desire, we convene scholars of media, literature, education, law, language, and sound to theorize accent as an object of inquiry, an interdisciplinary method, and an embodied practice.

The editors of Thinking with an Accent have compiled a media playlist to accompany the fifteen essays in our Open Access book, all of which are now available to read for free online or in a variety of downloadable formats from UC Press. We have chosen a range of media texts, spanning the realms of installation and video art, theater, fiction and documentary film, and music. Our goal, to borrow a phrase from pioneering raciolinguist John Baugh’s foreword to our volume, has been to channel the “methodological liberation that is on display throughout this book,” and to do so in a way that introduces readers to the work of each of our contributors.

Editor and contributor bios can be seen here.

The Freedom of Speech Itself (Lawrence Abu Hamdan, 2012)

Can a voice be frisked to determine the “true” origin of its accent? Lawrence Abu Hamdan has developed a body of work spanning critical essays, experimental documentaries, and installation art exploring this question. His 2012 work The Freedom of Speech Itself, comprising an audio documentary with foam-based sculptural voice-prints, examines LADO (Language Analysis for the Determination of Origin), a controversial practice of forensic accent analysis that has been employed by immigration authorities in the UK, EU, Australia, and Canada since the early 2000s to determine if asylum seekers without identification papers are in fact “from” where they say they are. Drawing on testimonies from asylum seekers, interpreters, forensic linguists, UK border control officers, and lawyers, Abu Hamdan teases out how raciolinguistic ideologies have become embedded in technologies of legal listening, which are in turn used to distinguish between those marked for citizenship, asylum, or deportation. An accent, he argues, is not a passport, but a living testament to an unstable and migratory lifestyle.

Abu Hamdan’s piece elaborates on issues explored in Michelle Pfeifer’s “‘The Native Ear’”: Accented Testimonial Desire and Asylum” and Nina Sun Eidsheim’s “Rewriting Algorithms for Just Recognition: From Digital Aural Redlining to Accent Activism.” Pfeifer develops the concept of the “native ear” to question naturalized assumptions about body, origin, and identity that pervade biometric linguistic analyses in asylum proceedings in Europe. Eidsheim studies how vocal synthesis, voice recognition, and voice-to-text technologies are algorithmically calibrated for, against, and in nonrecognition of certain accents. She describes these automated practices of accented listening as a form of “digital aural redlining” and her essay explores counterpractices that “jam” these technologies by cultivating listening capacities that “justly” recognize nonstandard accents. Leonardo Cardoso further explores how “accenting” emerges from the unexpected interactions and (mis)hearings among a heterogeneous network of human and nonhuman agents in his essay “Accentings, Acoustic Surveillance, and Political Crisis in 2010s Brazil.”

Disconnect (Anupama Chandrasekhar, 2010)

Anupama Chandrasekhar’s screenplay Disconnect recounts the working nights of three “last stage” debt collectors at BlitzTel call center in Chennai, India, in 2009. It explores various forms of connection and disconnection that result from India-based call center agents engaging with unseen Americans on the other end of the line. Disconnect was staged across the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and elsewhere between 2010 and 2013. In the play, the Indian agents take on American monikers, biographies, and attitudes, while putting on their best American accents to serve their Buffalo-based client, True Blue Capital. Disconnect offers a powerful and critical portrayal of accented speaking and listening, authenticity politics, and transnational interlocution in the 21st century. What is a “fake” American accent? Does an accent allow one to migrate virtually? In each scene of the play, viewers are invited to ask: To whom is the speaker speaking, and to whom is the listener listening? Read an interview with the playwright here.

Disconnect is discussed in Ragini Tharoor Srinivasan’s, “Is There a Call Center Literature?” Structured in accordance with the conventions of the partially automated call center, Srinivasan’s formally playful essay invites the reader to navigate a menu of options and artifacts drawn from her attempts to specify “Call Center Literature” – an accented rejoinder to the universalizing rubric of world literature. Also see Vijay Ramjattan’s “Accent Reduction as Raciolinguistic Pedagogy.” Ramjattan studies accent reduction programs marketed to skilled migrants in Canada and the United states, reframing accent as skill: as something someone does, and as a type of doing that can be used to reinforce as well as dismantle racist systems of oppression. The idea of accent as skill receives further elaboration in Sara Veronica Hinojos’s “‘Accented’ Latinx Textese: Bilingual Scriptural Economies and Digital Literacies.” Hinojos’s study of language choices and innovative shortcuts exults in the diverse, innovative visual vocabulary of bilingual Spanish-English texters.

Third Body (Zohar Melinek-Ezra and Roey Victoria Heifetz, Israel/Germany, 2020)

“There is something inherently euphoric,” writes Slava Greenberg, “about the awareness that one can intentionally and consciously change one’s voice. In his essay “Accenting the Trans Voice: Echoing Audio-Dysphoria,” Greenberg reflects on the experience of being mis-heard or mis-named over the phone as a source of audio-triggered dysphoria. The fixation of the listener on the audible traces of “elsewheres, elsewhens and elsewhos,” he writes, interrupts the trans-joy or audio-euphoria of experiencing his voice change on testosterone, pointing to the vulnerability of accented trans speakers to linguistic profiling and discrimination.

Greenberg’s essay revolves around a reading of a brief karaoke scene from the 2020 film Third Body, which portrays a day in the life of an Israeli trans woman living in Berlin. The karaoke scene is an interruption of the film’s nearly silent depiction of its nameless, silenced, and passive protagonist, as well as, in Greenberg’s reading, a temporary euphoric break from routinized audio-dysphoria. Singing along to Tina Turner’s “Private Dancer” in a private karaoke booth, she sounds herself into the world, temporarily safe from cis-sexist, ableist, and ethno-nationalist profiling. Third Body’s moving construction of a safe sonic home for its protagonist’s gender intentionality sits in contrast with David Thorpe’s efforts, documented in his film Do I Sound Gay? to rid himself of traces of the so-called “gay voice.” Ani Maitra’s essay “What Does it Mean to ‘Sound Gay’?: The (Accented) Voice as Surplus Jouissance” explores Thorpe’s reluctant identification with the culturally denigrated, but still commodified, feminine – and implicitly white – voice known as the “gay voice,” which Maitra reframes as a value-laden prosthesis that is simultaneously enjoyed and derided by its speakers and listeners.

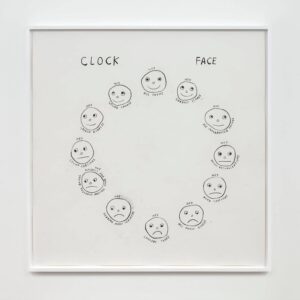

Trauma, LOL (Christine Sun Kim, 2021)

How do we map the distances between languages? How to address the isolation when we find ourselves stranded somewhere between them? Christine Sun Kim’s TRAUMA LOL emerged most directly from the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic and the protests of the Black Lives Matter movement. But as a Deaf Asian woman artist, she had been thinking and making art about the intersectional traumas of racist and ableist untranslatability for much longer. The title of the show charts the scales of different trauma, only to arrive at the absurdity of facing deep traumas that cannot be addressed. Kim says she is not “minimizing or making light of the trauma… LOL, as a response, very much comes as a reaction to being shell-shocked from this trauma. Trauma happens, and what do you do? You can address a small trauma, you can deal with it. But trauma upon trauma upon trauma? That starts to become LOL.”

TRAUMA LOL features charcoal infographic-like drawings of texts, emojis, and signs to devise a language that can communicate the emotional and psychological resonances of acquiring and losing specific written and signed languages. Kim’s art illuminates Lynn Hou’s and Rezenet Moges’ chapter “Sorry Hard Under Strong Accent” which also grows out of their personal experiences as Deaf Scholars of Color with white interpreters. It is not unexpected that Kim, as well as Hou and Moges, begin with the hardest task of translation: situating one’s use of language within shifting social contexts. Hou and Moges speak poignantly about the awkwardness of having their expertise as Deaf immigrant academics challenged by their interpreters who don’t understand them. Like Kim’s work, their essay draws attention to the specific modalities of a signed language that hearing subjects miss. They highlight accent as the distance between the modalities of hearing and signing where it is not simply phonetic but also lexical and bodily.

At their heart, Kim’s different drawings in TRAUMA LOL are also concerned with connection and seeking communication outside a specific language. Her use of infographics is critical to think other language. At the same time, discussing her drawings “America The Beautiful” and “Star-Spangled Banner” in an interview, Kim speaks about the conflict she felt when signing the national anthem at the 2020 Super Bowl. On the one hand, it was a great opportunity to use NFL’s platform. On the other hand, Francis Scott Key, the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” was a racist. Kim channeled her unease with the racist history and anger of the national anthem by notating a different version where she had pulled out some of the words, rearranging and reabsorbing them into other parts of the song. This seemed to her a better compromise than rejecting representing the anthem altogether. These glimmers of recognition and reckoning, thus, also offer an entry point into Akshya Saxena’s chapter “Stereo Accent: Reading, Writing, and Xenophilic Attunement,” which looks to accent for clues to solidarity and connection. In her discussion of Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis Trilogy, Saxena offers the phrase “xenophilic attunement” to explore how the distance between languages is often bridged by traveling together.

Mouth to Mouth (Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, 1975)

As an artist, performer, and writer, Cha often explored the complexities of language and communication, a reality of her multilingual upbringing as a Korean immigrant to San Francisco, where she learned English and French. Her work draws attention to the sensory experience of language and its relation to identity. Mouth to Mouth is an 8-minute video that uses speech to index displacement, uncertainty, and loss. In it, Cha captured her own mouth in an extreme close-up as she silently sounded out the eight Korean vowel graphemes. The sounds of water and snowy static fade in and out, making it hard to discern either the mouth or the sounds it produces. The overall effect is of eerie dissonance and confusion between what we see and expect to hear.

The fundamental instability of speech in Mouth to Mouth appears in several chapters in the volume. Particularly, Anita Starosta’s chapter, “Everything is Accented: Labor and the Weight of Things Unsaid,” invites readers to hear everything as accent. It explores how the temporary out-of-place-ness of accent renders it a powerful metaphor for the precarity of gendered and immigrant labor. Starosta writes that while the listener might hear accent as an index of identity, the speaker experiences it as a mark of “what he or she is not: not from here, not fully occupying any given present.” Thus, Starosta teases out a new relation between place and accent where as accent becomes audible in displacement, it also becomes endlessly replaceable. Her chapter helps us see the accented promise of the never-complete disappearance of Cha’s mouth, the intermittent visibility that accompanies the temporariness of accent.

Rey Chow’s chapter “Taking Accents Beyond Identity Politics? Thinking Through Two Paradigms” highlights the tension between accent as identity and the academic expertise that seeks to fix an accent to extract from it an identity politics. Chow begins her chapter with a discussion of a Chinese poem to stage the different paths to vocal recognizability that always mediate and split identity. She argues that “the self’s affective awareness of itself is audiovisually disjointed… [its] sentimental self-consciousness is entangled with other people’s mis- or non-recognition.” Watching Mouth to Mouth with Chow’s chapter offers a different perspective than Starosta as it invites us to consider the mediations that facilitate the event of accent. It returns us to the question animating the volume with an existential and political urgency, “What do we hear when we hear (our) accent?”

the clearing (JJJJJerome Ellis, 2021)

The final entry for the Thinking with an Accent media playlist is an experimental multimedia project by JJJJJerome Ellis, the clearing. This music album and book grew out of an essay Ellis published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies (2020). Ellis begins with his glottal blocks, those “silent, unpredictable gaps in speech” that he conceptualizes as “clearings.” In these moments of temporal suspension, he argues, anything is possible: clearings “open the present moment” such that other paths forward (linguistic and temporal) become available. Ellis’ music thus links dysfluency to Black histories and futures, and imagines other ways of conceptualizing time and healing from the violence of temporal subjection.

In including Ellis’ work in our playlist, we attempt to enact the coalitional politics that Pooja Rangan writes of in her essay “From ‘Handicap’ to Crip Curb Cut: Thinking Accent with Disability.” The coalitional model demands that we think in intersectional terms, not pitting one category against the other, or using one as a mere metaphor for the other, but instead training our attention on “the very social relations, conditions, values, and logics that trigger accent and disability oppression.” Ellis helps us draw connections between accented speech and stuttering, modes of voicing that are often understood as problems—as problems, moreover, that the speaker ought to correct. Like many of her fellow contributors, including Akshya Saxena (“xenophilic attunement”), Nina Sun Eidsheim (“aural redline jamming”), and Vijay Ramjattan (“counterpedagogies of institutional listening”), Pavitra Sundar reaches for an alternative to hegemonic notions of accent. In Sundar’s chapter, “Listening with an Accent–or How to Loeribari,” we are introduced to a “mode of audition that is keenly aware of its own vantage point” and that attempts “to go to, and listen from, a new or different place.” Ellis’ project offers a useful parallel to the spatial emphasis in Sundar’s essay, for the clearing unfolds the temporal possibilities of listening differently to (dysfluent) speech, and proposes a reframing of the experiences of becoming disabled, accented, and/or raced.

The ruminative music of the clearing makes room for listeners to reflect on, and revise, their habitual listening practices. As we dwell in the musical and conceptual brilliance of Ellis’ compositions, stereotypical and harmful associations of dysfluency and unintelligence or incompetence fall away. The telephonic call, once a site of danger and dread (due to potential for mishearings, misunderstandings, and misgenderings, as Slava Greenberg discusses) becomes instead a site of possibility. On track 7 of the album, “The Bookseller, Pt. 2,” Ellis reflects on why a bookseller hangs up on him when he first calls to order a book (track 4, “The Bookseller, Pt. 1”). He says: “something prevented the bookseller and I from gathering in the clearing.” With this simple statement, Ellis turns the scene of the “problem,” the telephonic exchange about a book, into the responsibility of both the speaker and the listener. Both of them must gather in the clearing in order for connection and communication to happen. The “happening” that is the accented/dysfluent speech is not a problem, but an opportunity for gathering.

***

This playlist reflects the work of the editors and contributors of the volume, Thinking with an Accent. Thanks to the following for assembling this playlist to animate their brilliant work:

Pooja Rangan is Associate Professor of English and Chair of Film and Media Studies at Amherst College. She is author of Immediations: The Humanitarian Impulse in Documentary (Duke University Press, 2017), which won the 2019 ACLA Harry Levin Prize for Outstanding First Book, as well as numerous articles on documentary ethics and politics, including, most recently, “Listening in Crip Time: Toward a Countertheory of Documentary Access” (Film Quarterly, 2022) and “Four Propositions on True Crime and Abolition” (with Brett Story, World Records, 2021). Rangan is working on her second book,The Documentary Audit, and a book on abolitionist documentary with Brett Story.

Akshya Saxena is an Assistant Professor of English at Vanderbilt University. Her first book, Vernacular English: Reading the Anglophone in Postcolonial India (Princeton University Press, 2022) explores the embodied and mediated ways in which English as a language becomes legible, visible, and audible in postcolonial India. Her scholarship has appeared in Cultural Critique,ariel, Interventions, Wasafiri, and South Asian Review.

Pavitra Sundar is Associate Professor of Literature at Hamilton College. Her work on the cultural politics of voice and media appears in Communication, Culture, and Critique; Jump Cut; Meridians; and the Sounding Out! blog, among other venues. She has coedited issues on masculinities (with Praseeda Gopinath,South Asian Popular Culture, 2020) and decolonial feminisms (with Debashree Mukherjee, Feminist Media Histories, 2022) and is author of Listening with a Feminist Ear: Soundwork in Bombay Cinema (University of Michigan Press, 2023).