Traces of psychotherapeutic drama and dream in the last works of David Bowie

By Leah Kardos (Kingston University)

(Cover Image Credit: Jimmy King, 2013)

This playlist is inspired by one of the themes that surfaces in my book Blackstar Theory: The last works of David Bowie (Bloomsbury Academic, 2022). The book takes a close look at Bowie’s ambitious last works: his surprise ‘comeback’ project The Next Day (2013), the off-Broadway musical Lazarus (2015), and Blackstar, the album that preceded the artist’s death in 2016 by two days. The last two of these projects were devised and completed secretly during the artist’s illness. The surprise announcement of his death on January 10, 2016, triggered a worldwide outpouring of grief. In a public statement made shortly after his passing, long-time friend and co-producer Tony Visconti confirmedthat he ‘knew for a year this was the way it would be’, adding ‘his death was no different from his life – a work of Art’.

These last works reference Bowie’s past, drawing ideas and imagery from earlier in his career– roles, costumes, gestures. And as to be expected, the works are inspired by and in dialogue with other theatrical art forms, especially pantomime, cinema, and teleplays. My research argues that in such work one can see what could be broadly described as ‘psychotherapeutic’ storytelling: narratives that play out in memory and dream spaces; and messy confrontations with iterations of the self in various types. This intertextuality that references his work and others, Bowie highlights the multiplicity of identity, and enacts a final healing and closure of his public performance persona.

Pierrot in Turquoise or The Looking Glass Murders 1970. Directed by Brian Mahoney. Scottish Television

Throughout his career, Bowie drew on stock characters symbolise the many and varied aspects of the self. He explained the approach in 1972: ‘I’m an actor, I play roles, fragments of myself’. A few years later he reiterated ‘I’m Pierrot. I’m Everyman. What I’m doing is theatre, and only theatre. What you see on stage isn’t sinister. It’s pure clown. I’m using myself as a canvas and trying to paint the truth of our time.’

Before he found fame as a musician, a young David Bowie studied dramatic arts (acting, mime, kabuki, and commedia dell’arte) under Lindsay Kemp at The Dance Centre in Covent Garden. In 1967 he took part in a pantomime called Pierrot in Turquoise, playing the role of the Cloud (the narrator), and writing and performing four songs for the show which starred Lindsay Kemp as the protagonist Pierrot, Annie Stainer as Columbine and Jack Birkett as Harlequin (the visually impaired dancer who would later become known his work in the films of Derek Jarman).

Pierrot in Turquoise premiered on 28 December 1967 in Oxford, and a filmed version was broadcast on Scottish TV in 1970 (dir. Brian Mahoney). In it, violence takes place in a mirror world; Pierrot exacts murderous revenge after Columbine spurns his love in favour of Harlequin.

Kemp’s unique Pierrot in Turquoise costume (seen in this clip, designed by Natasha Korniloff) pops up repeatedly over the years also. In 1969 it is pictured on the back cover of breakthrough release Space Oddity(illustrated by George Underwood), and was recreated (again by Korniloff) for Bowie’s 1980 music video Ashes to Ashes (dir. David Bowie & David Mallet. We see it again in Bowie’s self-directed 2013 video for ‘Love is Lost’.

Pierrot in Turquoise (1970) is available to stream on Vimeo.

‘Love is Lost (Hello Steve Reich Mix by James Murphy for the DFA – Edit)’ 2013. Directed David Bowie.

‘Love Is Lost’ was the fifth single from Bowie’s 24th studio LP The Next Day.

The music video was created by Bowie alone, costing a grand total $12.99, the price of the USB stick he needed to transfer the files to his computer. In the video, Bowie observes two of his past character creations in marionette puppet form – the Thin White Duke (c. 1975–6), a dark performance persona associated with fascist politics, and Pierrot the sad clown/everyman (from the 1967 panto/Space Oddity LP sleeve, and from the ‘Ashes to Ashes’ video in 1980).

The puppets act out a scene where the victim/antagonist role-play script is flipped – the one we presume to be dangerous is the only one who can see the situation clearly; the one we presume to be innocent might be concealing his malice. Bowie lingers in the background and anxiously washes his hands. The audience is left to decide which identity wins in the end, and at what cost.

‘Love is Lost’ was included in Lazarus the musical, where it is sung by the shadow figure Valentine, a violent and emotionally unstable man dressed in black. A dramatic ‘dun dun dun’ motif was added to the song’s introduction and bridge by Bowie, highlighting Valentine as the pantomime villain of the piece.

‘Love is Lost (Hello Steve Reich Mix by James Murphy for the DFA – Edit)’ is available to stream on YouTube.

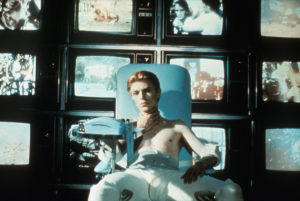

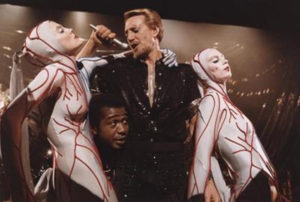

The Man Who Fell to Earth. 1976. Directed by Nicolas Roeg.

Lazarus the musical (2015), is written and presented as a sequel to Walter Tevis’s 1963 novel The Man Who Fell to Earth, though to make best sense of it, one needs to be aware of the book’s 1976 film adaptation directed by Nicolas Roeg (screenplay by Paul Mayersberg), in which David Bowie played the starring role. The 1976 film is a site of strange convergence – a place where Bowie’s identity and image became entangled with that of a tragic fictional extra-terrestrial called Thomas Jerome Newton.

In the story, Newton is sent to Earth to find a way to transport water back to his home planet, which is suffering from a severe draught. He fails his mission after falling prey to human vices and falling into a toxic relationship with a woman called Mary-Lou. After experiencing betrayals by the humans closest to him, Newton experiences a mental breakdown, is accidentally blinded by government testing, and in the final moments of the film, shown as a defeated alcoholic, living out his days alone in New York City. Bowie’s performance as the alien hinges on a subtle portrayal of disconnect, discomfort and distress. Roeg later told Time Out magazine (in 2011) that the reason Bowie was so successful playing the role was because he was essentially playing himself: ‘We really didn’t need to talk about the role at all; he was the part the moment he stepped on to the set … So much of that performance is simply Bowie being himself – and that’s what’s so brilliant about it!’

After filming, Bowie had a hard time shaking Newton from his system. His next two albums, Station to Station (1976) and Low (1977), explore themes of emotional detachment, psychic isolation, and personal distress, while the cover art for both albums are stills from the film, picturing Bowie in character as Newton. These too are the records most associated with Bowie’s personal battles with drug addiction and poor mental health in the 1970s.

The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) is available to rent online from the BFI website, and Amazon Prime Video. A sequel series, featuring Chiwetel Ejiofor and Bill Nighy was released on Showtime in April 2022.

Link to the official 1976 trailer on YouTube.

Cold Lazarus. 1996. Directed by Renny Rye. Channel 4.

Bowie’s musical Lazarus (co-written with Irish playwright Enda Walsh) completes Thomas Jerome Newton’s story, and according to Walsh, is set inside a ‘morphine dream’. In interviews Walsh cited the work of British dramatist Dennis Potter, specifically The Singing Detective (BBC 1986), as an important reference. Potter’s own swan song, his final interconnected works, Karaoke and Cold Lazarus (BBC and Channel 4 1996), also seem to have been explicitly referenced here also.

Potter’s final television dramas were completed in the decline of terminal cancer, produced and broadcast posthumously nearly two years after he died. Karaoke and Cold Lazarus share a central character, Daniel Feeld (played by Albert Finney), and are connected by themes of trauma, memory, death and redemption.

As Feeld faces the end of his natural life at the conclusion of Karaoke, he decides to allow his corpse to be frozen and preserved in a cryogenic facility in the hope that one day, once a cure for his illness has been found, he might be revived. Cold Lazarus is set 374 years in the future, where Feeld’s frozen head has been installed in a science lab to be mined for authentic memories and emotions. Trapped in this future dystopia and forced to repeatedly replay the troubling contents of his mind, it becomes evident that Feeld is aware of his situation and is begging to be put out of his misery. At the climax of the story the frozen head is mercifully destroyed along with the facility it was kept in. Feeld himself is granted a moment of transcendence as his memories play out one last time, now reversing back through his life, memories that could be drawn from Potter’s own life, his triumphs and traumas folding in upon a clear white light.

With this work, Potter managed to stage a resurrection of sorts, two years after his physical death. A Lazarus-style comeback that allowed him to continue to work and speak from beyond the grave and fictively perform the closure of his public life. Bowie pulled off a similar manoeuvre in the final months of his life with a stage play that continues to perform to packed out houses all over the world, continuing to perform a form of closure for his public life and his grieving fans.

Cold Lazarus, episode 4 ‘Finale’ (1996) is available to watch on YouTube. The whole series of Cold Lazarus is available to stream on Channel 4 (online).

‘Bye Bye Life’ finale sequence from All That Jazz. 1979. Directed by Bob Fosse. 20th Century Fox.

When explaining the genesis of the Lazarus script, co-writer Enda Walsh told the Financial Times that the pair ‘began to talk about death … about morphine. How the brain would wrestle with itself or what it would see in the moments before death. [Bowie said:] “Can we structure something about that?”.’ They talked about the psychotherapeutic noir of Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective and Bob Fosse’s cinematic ode to mortality All That Jazz (1979). ‘We discussed drugs and the drunken state a lot. How to construct something and place it behind the eyes of someone who is totally out of it. The film [Roeg’s adaptation] does it so brilliantly. We thought, we can do that on stage, too’.

In Bob Fosse’s semi-autobiographical fantasy All That Jazz (1979), protagonist Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) is ailing and, by the end, dying; inside his dreams he directs extravagant musical sequences starring his wife, daughter and mistress. After a series of heart attacks and undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery, these dream sequences become more elaborate and fantastical. As doctors try to save him on the operating table, he hallucinates a final show where everyone significant from his past is in attendance and he is able to thank them and say goodbye, the dream providing a moment of closure, forgiveness and healing that he was not able to achieve in his real life.

All That Jazz is available to stream on Amazon Prime video.

‘Life on Mars’ excerpt from Lazarus (dir. Ivo van Hove)

The staging of Lazarus at the New York Theatre Workshop, beginning in late 2015, was the fulfilment of a lifelong ambition for Bowie, who had tried many times in his career to create a rock musical without success up to this point. It came to pass just in time – he attended the premiere, what became his last public appearance, a mere four weeks and six days before his death. Lazarus portrays the stranded, substance-addicted alien Thomas Jerome Newton in a contemporary setting, tormented by visions and unable to die. Something is blocking his peace.

As the audience files into the venue, Newton is already on stage, lying motionless as if asleep or dead on the ground. He is half covered by a thin blanket and dressed in nondescript beige clothes that could be pyjamas. The story involves a visitation by a mysterious girl (played by Sophia Ann Caruso), who devises a plan to build a rocket ship using items from the apartment so that Newton can finally leave Earth; this takes form as an outline on the floor made with strips of masking tape. As Newton lies on the ground it creates the shape of a coffin surrounding his form.

At the show’s conclusion, after enduring a succession of frightening encounters with the shadow/villain Valentine, and once he has severed his attachment to his sad past, he assumes the same position in the middle of the floor as when he started, now able to finally find his peace.

‘Life on Mars’ live from Lazarus at the King Cross Theatre London (November 2016) is available to stream on YouTube. Soundtrack available on Spotify.

‘Lazarus’ 2016. Directed by Johan Renck.

The official music video for ‘Lazarus’ (the second single from the Blackstar album) was released on 7 January 2016, three days before Bowie died. In it, Bowie is shown lying in a solitary sick bed. His eyes are bandaged and it is clear from his gestures that he is anxious, gripping a blanket tightly to his chest. Among many things, the bandages could be seen as a reference to the conclusion of Tevis’s book The Man Who Fell To Earth, when the alien Newton is accidentally left blinded as a result of cruel government tests. The bandages are also associated with the ‘button eyes’ character from the ‘Blackstar’ video, which appeared before this, also directed by Renck.

There is another character in the ‘Lazarus’ music video, a creeping presence under the bed, played by dancer Elke Luyten. She points and gestures with tensed fingers towards the figure, threatening to pull him down below. Seemingly in response, he begins to rise, helplessly levitating from the bed. In the bridge of the song another version of Bowie appears, sans eye bandages, in front of a wardrobe. He’s dressed in familiar garb; a deliberate reference to a well-known image of Bowie from 1975, photographed by Steve Schapiro during the filming of The Man Who Fell To Earth, Bowie’s costume is all black, with white stripes painted diagonally across the front of his body.

‘Lazarus’ (2016) is available to stream on YouTube.

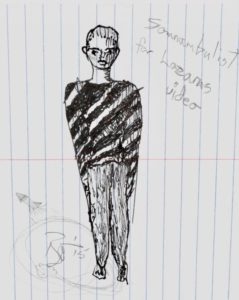

Sketch of ‘somnambulist for Lazarus video’. 2016, David Bowie Is… V&A.

A clue about the reprisal of the striped costume in the ‘Lazarus’ video found amongst the many notebook sketches included in the V&A’s touring David Bowie Is exhibition: a drawing of a male figure dressed in black covered in the characteristic white stripes, stood in the pose of the Kroisos Kouros, with the scribbled caption ‘Somnambulist for Lazarus video’. The striped somnambulist here appears to refer to 1920 silent horror film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari …

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. 1920. Directed by Robert Wiene. Decla Film.

The identification of the mysterious striped Bowie costume as the sleepwalker connects the image to the character of Cesare the somnambulist (played by Conrad Veidt) from the German expressionist silent horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), a favourite of Bowie’s and an identifiable visual reference in his work at other points in his career (Morley 2016). The wooden wardrobe of ‘Lazarus’ resembles the cabinet in which Cesare is kept in the 1920 film, from which he emerges to deliver his dire predictions of future events. Cesare’s costume is black from head to toe, form-fitting, with dusty white lines crisscrossing the front of his body. The unusually stiff way that Bowie’s somnambulist moves in the ‘Lazarus’ video seems to be also inspired by Veidt’s idiosyncratic physical movements in the film. The presence of a person asleep and dreaming is a motif that connects back to Lazarus the musical, specifically the troubling visions that emerge from our hero’s final reckoning in the unconscious realm.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) is available to stream on YouTube and Prime Video.

‘Blackstar’ 2015. Directed by Johan Renck.

The music video for ‘Blackstar’, devised by Bowie and directed by Johan Renck (Chernobyl), is a mashup of dark sci-fi and dream realism. It presents the artist alternately as a trembling blind man (the bandaged Button Eyes), a religious leader and a grinning trickster, and it strongly hints at Major Tom’s fate – the protagonist from Bowie’s first hit song (1969’s ‘Space Oddity’) is now a skeleton in a spacesuit, his bejewelled skull to be used as a relic in a strange ritual performed by a group of women. Nearby, three living scarecrows, all male, blindfolded with button eyes, are positioned in a grassy field, suggesting the scene of Jesus’ crucifixion. Eventually a surreal-looking monster, a black mass of dreadlocked fur and no face, is summoned. It rushes to attack the scarecrows with its large hook, while a heavy storm breaks over the town and the blindfolded Bowie character struggles and falters.

The music video for ‘Blackstar’, devised by Bowie and directed by Johan Renck (Chernobyl), is a mashup of dark sci-fi and dream realism. It presents the artist alternately as a trembling blind man (the bandaged Button Eyes), a religious leader and a grinning trickster, and it strongly hints at Major Tom’s fate – the protagonist from Bowie’s first hit song (1969’s ‘Space Oddity’) is now a skeleton in a spacesuit, his bejewelled skull to be used as a relic in a strange ritual performed by a group of women. Nearby, three living scarecrows, all male, blindfolded with button eyes, are positioned in a grassy field, suggesting the scene of Jesus’ crucifixion. Eventually a surreal-looking monster, a black mass of dreadlocked fur and no face, is summoned. It rushes to attack the scarecrows with its large hook, while a heavy storm breaks over the town and the blindfolded Bowie character struggles and falters.

In making this video Bowie and Renck reportedly bonded over shared interests in surrealist film and work of directors such as Alejandro Jodorowsky and Andrei Tarkovsky. The influence of German expressionism is also apparent in the composition and staging of the exterior scenes – the stylised alien landscape with its curled edges, the ancient town lit from the centre, with its symmetrical buildings in perspective, call to mind the set designs from the silent films of Robert Wiene and Fritz Lang.

The image of Bowie’s bandaged, frightened Button Eyes character coheres with Lazarus the musical, the music video for ‘Lazarus’, and the legacy story from The Man Who Fell To Earth. The image also prods at our anxieties about death and what comes next, how it feels to not be able to see a future. On the 1972 album Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, the opening song ‘Five Years’ describes how the news of an impending extinction event for humanity in five years’ time feels: “We’ve got five years / stuck on my eyes”.

Being diagnosed with life-threatening/terminal illness is a cruel knowledge to receive; a paradoxical trade-off where one is forced to surrender knowledge of the future in exchange for the kind of unnatural knowledge no-one would want to possess – how much (or little) time there is left.

‘Blackstar’ (2015) is available to stream on YouTube.

—-

Bio: Leah Kardos is a senior lecturer in music at Kingston University London, UK, where she co-founded the Visconti Studio with music producer Tony Visconti. She specializes in the areas of record production, pop aesthetics, and exploring interdisciplinary approaches to creative practice. Critical and musicological study of the work of David Bowie is an area of special interest. In 2019 she started the Kingston University Stylophone Orchestra, the only ensemble of its kind in the world. Leah also writes music criticism and book reviews for The Wire.