(Featured image: Art by Lids Bierenday)

Screening Sexual Provocation

Sex sells. It’s an age-old axiom but one that has gained renewed force within the contemporary era, as creators increasingly turn to provocative sexual content to generate buzz and stand out within a glut of programming. In my new book Provocauteurs and Provocations: Selling Sex in 21st Century Media (Indiana University Press, 2021), I look at the provocative in films, television series, web series and videos, entertainment industry publicity materials, and social media discourses over the last twenty years to consider how sexual provocation functions as promotional strategy within the fragmented, cluttered contemporary mediascape, and encourages the branding of media creators as “provocauteurs” known for challenging sexual and representational conventions.

With new distribution technologies enabling and amplifying these provocations, some such deployments may be “sexploitative” in their sensationalist attempts to capture eyeballs and profits, ultimately commodifying and containing their transgressiveness. Yet there is always the potential for these provocative artists and works to resist sexual hegemonies by envisioning alternative ways of screening and imagining our cultural logics of desire. Seeking to recover the political force of the provocative, I contemplate how certain of these provocauteurs and provocations engage controversy as a means of resisting representational and ideological norms around sex and sexuality.

The titles that follow, selected from among those I analyze in the book, are chosen with an eye to encapsulating each chapter with a representative work (or two) of sexual provocation.

Je Tu Il Elle (Chantal Akerman, 1976)

Akerman’s first feature, made at the age of 24, remains the standard bearer for Sapphic sex scenes. As my prologue “Tangled up in Blue” discusses – in regard to its influence on Blue Is the Warmest Color – Akerman’s balance of stylized distanciation and hyper-intimate immediacy make for, as Patricia White has described it, a “raw and still unmatched sex scene” (2008: 416).[1] More astounding is its length, which at thirteen minutes is nearly double that of all the sex scenes combined in Blue, which has double the running time. And yet the film’s first two-thirds, involving Akerman’s alter ego’s compulsive sugar consumption and a handjob she gives a trucker played by Niels Arestrup, are more provocative still.

Stream Je Tu Il Elle on Criterion Channel.

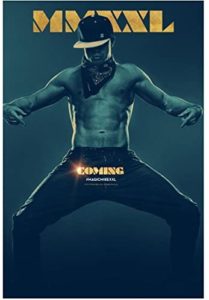

Magic Mike XXL (Gregory Jacobs, 2015)

Though it dispensed with its predecessor’s recession-era socioeconomic critique and dared to alienate the gay fanbase that had made the first installment a gargantuan sleeper hit, this supersized sequel doubled down on its beefcake billing and coy come-ons, doing what virtually no contemporary Hollywood movies dare in declaring “This one’s for the ladies,” and saw a deluge of dollars rain down. In so doing, it proved an exemplar of what my introductory chapter names the “millennial watercooler movie,” by revitalizing the theatrical market for adult cinema and moviegoing as a public sex culture (not to mention spearheading a lucrative side hustle in girls’ night/bachelorette viewing parties and live shows) in an era of family films and fantasy franchises.

Magic Mike XXL is widely available for rental and is also currently streaming on Amazon Prime.

In the Cut (Jane Campion, 2001)

Arguably no filmmaker – certainly no woman filmmaker – has done more to demystify the penis as Campion, whose leading men and women have over the course of her three-decade career consistently been game to go full-frontal within explicit sex scenes that reveal and reverse gendered dynamics of power and (visual) pleasure. Together with works by and about gay men (HBO’s Looking and Alain Guiraudie’s Stranger by the Lake), In the Cut serves as a key case study for my chapter devoted to sifting through the recent proliferation of male nudity onscreen to locate works that achieve de-fetishization through representation.

In the Cut is widely available for rental in both its R-rated theatrical and (recommended) unrated versions (for example, on BFI player), and is also currently streaming on Mubi.

Double feature: The Fountain (Lena Dunham, 2007), À ma soeur (Fat Girl, Catherine Breillat, 2001)

Self-proclaimed “pariah of French cinema,” whom I designate (with my own coinage) a “provocauteur” extraordinaire, Breillat has courted controversy since she was a teenage memoirist, never more than when she turns her sights on the simultaneous sanctification and sexualization with which our culture views adolescent girls. Her autobiographically-inflected Fat Girl seems an all too prescient predictor of contemporary cultural conversations around consent and sexual assault. Taking a cue from Breillat, Lena Dunham’s stoking of her haters, sustained through six seasons of Girls, saw its earliest pile-on in the YouTube comments section of her film The Fountain, where the vitriol spewed only supported its college-aged creator becoming an overnight sensation.

Stream The Fountain on Criterion Channel; rent/stream Fat Girl on Amazon Prime, Apple iTunes, Criterion Channel, and Vudu.

Laurel Canyon (Lisa Cholodenko, 2002)

Cholodenko’s underseen ensemble drama is headed by a never-cooler Frances McDormand as a prominent music producer shacked up with her much-younger rocker boyfriend (a never-hotter Alessandro Nivola), who’s forced to reckon with parental responsibility when her estranged son (Christian Bale) comes to stay, accompanied by his brainy fiancée (Kate Beckinsale). Perhaps Cholodenko’s biggest provocation was in following up her breakout first feature High Art (1998), a landmark of lesbian filmmaking and high point of New Queer Cinema, with a decidedly LGBT-free work that appeared to confirm her mainstream aspirations. Poke a little further, and its queer-connoting contemplation of the ethics of alternative relationships emerges, most memorably in Bale and Natascha McElhone’s playing out their pact of sexual sublimation, surely the steamiest scene ever set in a Volvo and with nary an item of clothing removed.

Rent Laurel Canyon on Amazon Prime, Google Play, Microsoft Store, Vudu, and YouTube.

Appropriate Behavior (Desiree Akhavan, 2014)

Akhavan’s retelling (read: reappropriation) of “radical romcom” Annie Hall puts the (as I call it) “bad queer” back in queer cinema, insofar as her un-PC sensibility and inbetweener straddling of gay and straight worlds defy LGBTQ cultural scripts and identity policing. Akhavan does Allen one better by displacing our sympathy and the film’s perspective onto the protégé – her bisexual Iranian-American alter ego Shirin – rather than the holier-than-thou partner who pronounces their relationship “just a phase.” In all ways a welcome departure from the anodyne coming out narratives predominant since the 90s, its unblinking approach to treating sexuality on screen has as its cringe-inducing centerpiece a threesome that devolves from arousing to supremely awkward.

Rent Appropriate Behavior on Amazon Prime, Apple iTunes, and FandangoNOW.

Bonus watch: “It Gets Better?” (2011). Akhavan and (former collaborator and partner) Ingrid Jungermann’s snarky takedown of the early 2010s viral PSA project earnestly devoted to “inspiring LGBTQ+ youth” is a standout even among the addictively irreverent episodes of their pioneering web series The Slope (2010-2012). All two seasons’ worth of its “superficial, homophobic” brilliance are available to stream free on Vimeo.

“Cat Person”, by Kristen Roupenian (New Yorker, December 11, 2017)

Now two decades into the new millennium, I turn at book’s close to ask “what’s still taboo?” As my epilogue elucidates, caught between the buffering effects of irony and social media opprobrium for “going too far,” the convergence of old and new media erupted with the Twitterstorm around Roupenian’s short story. Like last year’s similarly productive exchanges in the wake of “WAP” going viral, at the heart of this work heard round the internet was the articulation of what constitutes, for women, satisfying sexual encounters – even circa 2020, it seems, still a provocation.

As an added enticement, view the trailer for Provocauteurs and Provocations: Screening Sex in 21st Century Media. If this leaves you wanting more – and I hope it does! – please visit the press’s website through May 2021 to receive a 30% discount on both of my IUP titles using promo code SANFILIPPO.

And lest you imagine 2020’s global pandemic put sexual provocation on hold, read my follow-up piece “The Year of Screening Provocatively.”

[1] Patricia White, “Lesbian Minor Cinemas,” Screen 49.4 (Winter 2008) 410-425.

***

Maria San Filippo is Associate Professor in the Department of Visual and Media Arts at Emerson College, and editor of New Review of Film and Television Studies. She is author of the Lambda Literary Award-winning book The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television (Indiana University Press, 2013) and editor of the forthcoming collection After “Happily Ever After”: Romantic Comedy in the Post-Romantic Age (Wayne State University Press, 2021).