The global pandemic of Covid-19 has brought with it a pandemic of viral misinformation, or information from the top down. How can media, and in particular, the domestic and socially distanced media, combat this spread? From Dale Hudson (NYU Abu Dhabi) and Patricia R. Zimmermann (Ithaca College) a reflection and list:

First Wave COVID-19 Playlist: Information

The coronavirus pandemic has propelled a neoliberal migration of education, business, leisure, news, arts, and personal life online. Corporate software has thoroughly infiltrated domestic spaces. Many interpersonal relationships are visible and audible only on screens. Some aspects of life transfer relatively well, but other areas risk abandonment.

Arthouse cinemas struggle to reinvent themselves as curated streaming platforms. Restaurants partner with delivery services. The world struggles to reinvent as though pre-COVID-19 social practices can be reconstructed online. In times of crisis, many people look for distraction from the difficult-to-digest reality that post-COVID-19 life will not entail returning to “normal” in a few months or years.

While revisiting the past by streaming recorded performances at operas or concert halls or by convening “watch parties” for favorite films holds value, staying with the trouble of the present is urgent. It is imperative to communicate useful and accurate information.

How can media communicate useful information when we need social distancing to limit the spread of the coronavirus? How can we evaluate which sources provide accurate and useful information?

For decades, activists around the world have warned about the implications of the shift to remote communication and how it exposes the depths of corporate control over every aspect of our lives. Although this shift can inhibit or even prohibit sharing information, it can also facilitate sharing information that official state or professional news agencies fail to include or deliberately exclude.

The pandemic has thus also involved a migration of information from corporate and state agencies to citizen, community, and participatory media. CNN runs special two-hour town halls with experts, but the cable network regularly and consistently rejoices over acts of corporate charity in what might be called corporate service announcements, rather than public service announcements. This free corporate publicity distracts from recognizing how states fail their citizens and noncitizen residents. These feel-good phantasmatics about corporations are actually part of the problem. Neither corporations nor corporate news are not altruistic institutions.

When states fail to lead or regulate corporations, people step up.

Some, however, are well intended but ill equipped. Rumors go viral across social media in what are termed “infodemics.” Confusions multiply and accelerate. As a result, some people mistrust the news media.

To counter mistrust, citizen, community, and participatory media have become increasingly crucial. Media-literacy campaigns that fact check stories, circulate through social media. To counter misinformation, activist and community media organizations redouble their attention on media literacy. They mobilize data visualizations and animations to convey the significance of scientific data, marshalling strategies comprehensible to nonscientists.

the media that matters most often emerges on a small scale.

The small scale of this media contrasts with the enormous dimensions of the pandemic. While the pandemic is global, the experience of it and the media chronicling it are resolutely local because people cannot safely gather together.

Screen media is now less visible and audible as part of a shared environment. Before the pandemic, sounds and images intruded into the mental spaces of passersby with the large screens and projections in urban centers or the smaller screens mounted in government buildings, stores, airports, train, and bus stations. Now, this media landscape becomes almost entirely domestic, reduced to the small screens of mobile devices and laptops typically held in the hand of a single individual.

The scale and scope of media contracts to small, short, accessible, and often nonprofessional iterations, but its makers infiltrate platforms and technological interfaces, whose scope and scale is often unimaginable. For production and distribution, they hack proprietary technologies by any means necessary. Ones developed to facilitate both communication and surveillance become platforms to interrogate official responses, work through understanding scientific information, and present different perspectives.

Although they operate across software and hardware controlled by corporations, such as Alibaba (Youku, Toduo), Alphabet (YouTube, Google Hangouts, Gmail), Cisco (WebEx), Facebook (Instagram, WhatsApp), Renren, TenCent (WeChat, Weibo, QQ), Skype, and Twitter, they also carve out spaces for semi-public debate.

These small local media appropriate the technologies of large corporations to facilitate both local and global connections. They spread and circulate information virally through mediated person-to-person contact.

aoc IGTV (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, United States, 2020)

https://www.instagram.com/aoc/channel/

As the older white men in US politics staged their official press conferences for television broadcast, congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez from New York’s 14th district took to Instagram and other social media platforms. Her media strategy connects the problems of the pandemic to the antidemocratic structures inherent in US governance. Social and environmental justice propel pandemic justice.

She speaks directly to her 4.4 million followers. She does not discuss the symptoms of the pandemic but instead focuses on the underlying causes for its devastation of people in her district, numbers exceeding any other in the United States. The contrast between her IGTV (Instagram television) posts and the two-hour press conferences by the US President Donald Trump and with New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo is more than generational. It is political. She converses directly with voters, free from rating-driven filters of much television news.

The two-minute “When it comes to COVID-19 , inequality IS a pre-existing condition” (18 April 2020), edits professional news footage with Ocasio-Cortez’s original footage shot on her phone. Rather than masking vertically-framed video from a mobile to look like the horizontally-framed video format of professional media. this piece maintains a visual style that facilitates how most people actually hold their mobiles.

The content departs from political press conferences that are designed for television and print news reporters to summarize into sound bites. In contrast, she delves into the underlying causes of the pandemic, and demands that her followers volunteer at phone banks or donate to food pantries. The video eschews the “we’re all in this together” phantasmatic.

Ocasio-Cortez links the effects of the pandemic with systemic inequality. A lack of universal healthcare throughout most of the United States accelerates and amplifies the impact of COVID-19. The underlying causes for the crisis are structural. Problems are not limited the absence of PPE (personal protective equipment) and scarcity of incubators as many governors contend. Unfair wages, unfair access to employer-sponsored healthcare, and unfair exposure to toxic dumps persist as structural problems of health disparities.

The virus will not be cured “like a miracle,” as US president Donald Trump suggested, nor will structural racism that makes certain populations more vulnerable to the virus and to dying from it be cured wondrously. Systemic injustice renders The Bronx and Queens residents in Ocasio-Cortez’s district more vulnerable than those places in across New York State and the United States. Half are immigrants, who pay taxes but are excluded from US politics.

Residents in her congressional district are primarily African American and Latino American, with inadequate access to healthcare. Ocasio-Cortez emphasizes that healthcare is a human right. She proposes a multi-pronged response that includes building safety in communities to avoid panic and fear. She proposes responding with “permanent systems and structures, so that we do not find ourselves in this fragile of a position again.” She calls for “bold moral leadership” to ensure that “we abolish these systems of injustice, abolish these systems of class warfare” to center on “people and working-class Americans.”

In the seven-minute, “Weighing vote” (16 May 2020), Ocasio-Cortez outlines her conflicted response to a proposed coronavirus relief bill, as she awaits her turn to vote and asks for constituent feedback. Wearing a mask emblazoned with #MedicareForAll, she expands her face-to-face interactions with citizens and residents of her district through social media. She responds to questions posted on her feed. She demystifies the political process rather than grandstanding about saving the world like old patriarch. She informs her constituents that they have to act.

Ocasio-Cortez defeated longtime congressman Joe Crowley in 2019. Her election was part of a wave of progressive women who became first-term members of the US Congress’s lower house. Aligned with Wall Street more than Main Street (small business and citizens), the Democratic National Congress immediately recognized her as a threat. Social media allows her to bypass the corporate gatekeepers of CNN, MSNBC, and Fox. It also provides a platform for her to speak and listen to with her constituents in real time during moments of urgency.

Collecting Wales Covid Experience/Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru (The National Library of Wales, Wales, 2020)

The National Library of Wales initiated an open archive to gather photos, videos, letters, recording, journals, voice memos, and diaries from people around the world that reflect upon their experience of the pandemic and efforts to contain it.

The project serves as an ongoing open archive to chronicle the impact of COVID-19 on the daily lives of people. It also includes newspapers, citizen journalism, and news from state or corporate sources.

The library has a list of suggested questions contributors might ponder as a way to reflect upon their experiences, such as “How is your day at the moment and how does this compare to your usual day previously?” and “What have you done to try and deal with the situation?”

These videos fill the gaps in reporting by professional news services.

https://www.library.wales/about-nlw/work-with-us/collecting-wales-covid-19-experience

Corona Diaries: Open Source Audio Stories from around the Globe (Uli Köppen and Fran Panetta with Tanja Proebstl, James Burke, and Halsey Burgund, Germany/United States, 2020)

Corona Diaries is an open-source platform, aggregating short audio files of no more than two minutes in duration that contain personal stories of the pandemic crisis. The project emphasizes the importance of short audio testimonies to lower the barrier to entry for participation and also to capture nuance and tone that can be lost or hidden in written form. The website explains that the project “documents the pandemic through personal stories—big and small. All stories are welcome.” It says it is “forever growing and always accessible.”

The website is divided into three section with single-word titles that simplify the task of addressing the pandemic in all of its complexities: about, listen, speak. It includes a world map, indicating where stories have been uploaded. Clicking the marker activates the story. To date, stories have been shares by people in Austria, Brazil, Canada, Italy, Nigeria, Peru, Saudi Arabia, Spain, South Korea, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States, and elsewhere.

Corona Diaries makes recordings from artists to journalists to students, from mothers and fathers to employees and employers, available to anyone with internet access for download and use under a Creative Commons license.

Corona Diaries is a Nieman Foundation Project, initiated by the 2019 Nieman Fellows and sound artist Halsey Burgund.

Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) Explained through 3D Medical Animation (Scientific Animations, United States, 2020)

Published on YouTube on 11 February 2020, this six-minute animation offers information on four topics: what is a pandemic, how this coronavirus spreads, how coronavirus attacks the body, and what are recommended precautions to protect against pandemics. It adopts the style of an educational documentary.

The video’s style moves between professionally-rendered 3D animation and what looks like PowerPoint slides by a novice. Its white-male–sounding voiceover explains information without the sensationalism of commercial news media. At times, it sounds computer generated.

At the time of the video’s production, the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV, now commonly COVID-19) had spread to become a pandemic like the influenza virus of 1918. Two other strains of coronavirus became regional epidemics: SARS (2001–2003) and MERS (2012–2015), resulting in over 15,000 deaths.

Unlike these coronaviruses, this one was believed to be transmittable during the incubation stage, thus prompting scientists to imagine that the 40,000 cases in China were substantially lower than cases worldwide. In this viral context, effective communication of scientific information is vital.

The medical animation translates biology into a comprehensible narrative for non-scientists. Charts of the coronavirus structure are labeled while the voice-over uses language accessible to nonscientists. The genetic material “allows the virus to hijack human cells, turning them into virus factories.” Ultimately, the human cells die.

Because there is no cure or treatment, preventing transmission by air or touch is essential. The video outlines behaviors that are normal in most parts of the world to prevent the spread of the flu: washing hands regularly, wearing masks and gloves, covering coughs and sneezes with elbow (rather than hands), avoiding high-contact surfaces, and not sharing towels or eating utensils.

This information is particularly urgent for populations in the United Kingdom and United States, where politicians belittled scientists before the numbers of infections and deaths became too large to deny. It is also critical for populations in places with questionable public health policies, such as Brazil, Russia, and Sweden.

Although some of the information, such as a recommended distance of “2 to 3 feet” (that is, less than a meter) from someone sneezing or coughing, has been updated in light of newer data that recommends social distancing of two meters, the animation remains useful. The video’s cautionary ending about preventing a pandemic continues to haunt.

The animation is tagged with links to downloadable information and links to webpages with additional resources.

Global COVID-19 Tracker and Interactive Charts (1point3acres, China/United States, 2020)

Developed by Yu Gao, a graduate of Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who is originally from Wuhan, 1point3acres is a website that initially tracked the spread of COVID-19 in Canada and the United States. It has subsequently expanded to function as a global dashboard for tracking the pandemic, providing real-time updates from credible sources, using data crawlers, API calls, user submissions—all of which are cross-referenced. Information is updated every five to fifteen minutes.

Among Yu’s collaborators are first-generation Chinese immigrants and Chinese students. The site fights against the racist discourses that label COVID-19 the “China virus,” “Wuhan virus,” or “Kung Flu.” This anti-racism dimension of the website is important given President Trump’s effort to project the blame China for the pandemic’s devastation of the United States, thus avoiding responsibility for not doing more to prevent the virus’s transmission. To date (June 2020), almost 120,000 people have died in the United States alone.

The website is organized into six areas, all of which are presented with clarity and accessibility: summary, map, news and live updates, supplies, trends, and videos. Information is offered in Chinese, English, French, Japanese, and Spanish.

The site offers subareas, featuring facts and aggregated information. In the Work and Life subsection, it posts information on policies of various companies for working from home. The School subsection lists colleges and universities as they migrate to remote teaching. The What’s in Stock section lists grocery stores and categories such as “busy,” “fruit and vegetables,” and “meat, fish, and eggs.” The Testing subsection provides real-time data on testing locations, pending cases, positive, and negative cases.

As its designers and engineers emphasize, the site organizes data to be used during the crisis, but it is designed for people not specialists. It also reminds us that behind the data visualizations are real people, who are themselves confronting COVID-19.

COVID-19 Response Hub (WITNESS Media Lab, United Kingdom, 2020)

WITNESS Media Lab has launched the COVID-19 Response Hub “to protect human rights during this pandemic.” It provides guides, tips, resources, and best practices on creating, sharing, and collecting videos during the pandemic crisis. According to its website, it highlights “videos from around the world that are exposing the unseen impacts of this crisis and telling stories that some governments would prefer remain hidden” in sites that include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Kenya, Philippines, and United States.

The site explains that WITNESS wants to facilitate the ability of citizen (and noncitizen) journalists and video makers “to expose and make visible stories authorities trying to hide, abuses justified by quarantines, disparate impacts on marginalizes populations.” WITNESS has a long commitment to protecting individuals and groups who come forward with information of human-rights violation that are deemed sensitive or controversial by state and corporate entities.

In a companion essay about the website entitled “Coronavirus and Human Rights,” Sam Gregory of WITNESS argues that direct documentation of abuses is needed during this crisis moment to chronicle quarantines, enhanced emergency powers, restrictions on sharing information, government repression, and violations by private actors. He notes a dangerous escalation by social media companies to algorithmic moderation and control of what users post and share.

The essay reminds us that many people in land rights and environmental justice movements around the globe, notably the Amazon, Burma, Kashmir, and Palestine, have already been living in a crisis that pre-dates COVID-19. He ends the essay encouraging activists and citizens to “discover new ways to act in solidarity and agency with each other online,” and to physically distanced, yet still social proximate.”

#COVID-19: The Social Media Pandemic (CNA, Singapore, 2020)

Produced by the English-language new channel CNA in Singapore, this forty-seven-minute documentary guides users through the viral spread of information in billions of posts on COVID-19 that became a “social media pandemic.” It charts a history of kneejerk reactions and thoughtful responses to the virus across Hong Kong, London, New York, Singapore, Wuhan, and other places.

The documentary uses the conventional blurred backgrounds for portrait-oriented video from mobile phones, but it also maps landscape-oriented video onto an image of a laptop before cutting to the actual video in order to identify it as non-broadcast media. It animates the “likes” and “loves,” familiar on social media. The documentary’s visual style is designed for social media users.

More significant, however, is the content. It narrates a story of panic and confusion but also moments of hope and clarity which begins with the world’s largest migration of people to celebrate the 10 January 2020 Lunar New Year. As rumors began to spread, CCTV live-streamed the ten-day rapid construction of Wuhan Huoshenshan and Leishenshan hospitals to calm anxieties, a very different approach than Italy, Iran, United Kingdom, or United States.

At its worst, social media seems to encourage spreading racism and xenophobia against Chinese, hoarding toilet paper and surgical masks, selling PPE (personal protective equipment) at exorbitant prices, and promoting unverified information that caused deaths in Iran and Indonesia. Most egregiously, the US president promoted the malaria medication hydroxychloroquine, resulting in accidental deaths in the United States and as far away as Nigeria.

At its best, social media inspires humans to become active netizens. Farmers crowdsource permissions to delivery 500 kilograms of fresh vegetables to Wuhan in lockdown. Nurses transform TikTok videos into public health information aimed at young people. Hashtags challenge people to be brave and treat one another better.

The documentary advocates learning to share information for the common good. As Hong Kong-based Chinese vlogger Yang Yuli makes clear, Wuhan residents have much to teach the rest of the world about living in lockdown, managing self-quarantines, and learning to fact check information.

Covidiots — “Reopen Wisconsin” Rally 4/24/2020 — Covidbot (Oblivion Art, United States, 2020)

Resistance to power takes multiple forms, ranging from progressive to reactionary. With public health policies issues by each of the fifty US states, the federal government was able to shirk responsibility for a national approach in the name of “state rights,” a frequent dog whistle to libertarian and nationalist groups.

During the #letssharecovid19 (Let’s Share COVID-19) rally on 24 April 2020, a remote-controlled model of the coronavirus—later dubbed “Covidbot”—moved through humans, largely un-masked and bunched together without the recommended distance of two meters.

As protestors snapped images of it, the Covidbot moved through an anti-lockdown rally in the midwestern state of Wisconsin, one of the key battlegrounds in the 2016 presidential election that was largely ignored by the Hillary Clinton campaign but visited by Donald Trump campaign on the day before the election.

While the Covidbot did not seem to elicit the sort of thoughtful discussion that disruptive performances are intended to produce, it was documented on video, which spread virally, so the performance might prompt politicians to remember that voters remain ill- and under-informed on public health, if not in the United States, perhaps elsewhere. Oblivion Art uploaded the video to YouTube.

Drone Footage Shows Wuhan under Lockdown (ChinaFile, China, 2020)

An emerging genre of aerial footage shot from drones over cities under lockdown is becoming pervasive across the globe. This particular drone footage of Wuhan, where the COVID-19 crisis began and where citizens first experienced shelter-in-place orders, circulated virally and ended up on the New York Times site.

In aerial tracking shots in long takes, the drones fly over empty cities, an elegy for the people that formerly congregated on sidewalks, cars and trucks that once jammed streets, and airplanes that ordinarily would be taxing on tarmacs. The drones chronicle the excesses of the built environment as the ruins and remains of global capital in a pandemic, peppered with a lone car or person or bicyclist.

The tension between modern structures, built for movement, and their stasis, when not in use, is a reminder of the fragilities and precarities of human species as a consequence of environmental devastation, carbon emissions, and other causes of the deadly Anthropocene. The effect would be less chilling in other cities around the world, where infrastructure is already crumbling, so that a city under lockdown looks more like abandoned ruins.

Engage Media Coronavirus Series (Engage Media, Indonesia/Thailand/Philippines/Australia, 2020)

#Coronavirus: Infodemic (EM News, Philippines, 18 March 2020)

#Coronavirus: Protecting Yourself (EM News, Philippines, 31 March 2020)

#Coronavirus: Disinformation (EM News, Philippines, 31 March 2020)

Manila’s Poor Under Lockdown (EM News, Philippines, 14 April 2020)

Shooting Covid-19: Media Frontliners in Manila (EM News, Philippines, 06 May 2020)

Produced by EngageMedia, these short videos provide a view of the impact of coronavirus on the ground in the Philippines. They look at the impact on poor communities, street vendors, jeepney drivers, community kitchens, and the homeless.

Several of the videos, produced in collaboration with Vera Files under the three-part series name #Coronavirus, deal with serious public health issues of face masks, hand washing, disinformation, and infodemics. They educate viewers always to check their sources and to consult the World Health Organization (WHO), credible health authorities, and the media for accurate information.

In #Coronoavirus: Infodemic, editor and reporter Celine Isabelle Samson examines confirmation bias that is produced by—and reproduces in—racism and Sinophobia, effecting Chinese nationals, who come to work in the Philippines, and also the Chinese Filipino community. In the absence of official information, social media produces an overabundance of unreliable, inaccurate, or unverified information. Viewers are encouraged to submit stories for a fact check.

#Coronoavirus: Disinformation examine media stories about wet markets that sell wild animals in Wuhan (represented with images of markets in Indonesia), and scientists who linked COVID-19 to bats (its origin remains undetermined at this time). #Coronoavirus: Protecting Yourself instructs on how to wear masks and wash hands. Vera Files is “powered by” USAID.

Based in Indonesia and Australia with team members in Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines, EngageMedia is a nonprofit media, technology, and culture organization, focused on social change and environmental justice through participant and citizens video that are produced to circulate through social media and other networks.

Videos are produced by independent filmmakers, journalists, technologists, campaigners, and social movements, then uploaded on the EngageMedia website, which functions as a portal to community media produced in the Asia Pacific and Southeast Asia.

Governor Andrew Cuomo Daily Coronavirus Briefings (State of New York, United States, 2020)

New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo daily briefings on the coronavirus pandemic have garnered a national and international attention and an almost cult-like following because they stand in direct opposition to the misinformation and disinformation of the Trump administration.

Their slow delivery in one long take, accompanied by a well-designed PowerPoint slides, contrasts with what many find to be the alarmist animations and sensational music on CNN or Fox. Cuomo sits at a long table, flanked by doctors and public health officials, spread about two meters apart.

In US politics, Cuomo had a reputation as a bully, tinged with corruption, much like other long-serving members of the Democratic Party. His press conferences, however, show him as a public servant, dedicated to facts, evidence, and action to protect the people in the State of New York, among the hardest hit in the global pandemic.

His blue-and-gold PowerPoint presentations, replete with graphs, data, inspirational quotes, pictures of essential workers, and directives on mask wearing and hand washing convey statistical information on the spread and containment of the virus in a clear way as a compelling form of public health communication.

Roma città chiusa/Rome, Closed City (Mo Scarpelli, Italy, 2020)

Posted on 13 March 2020, the video opens with the sounds of birds over images of empty streets lined by graffiti and trees without leaves. Rome appears even more desolate that the city under Nazi occupation, captured in Roberto Rossellini’s neorealist Roma città aperta/Rome Open City (1945).

Human presence enters through the sounds of a tram. When it stops, no one exits or enters. One passenger wearing a mask can be seen inside it. The video moves to shots of written and printed artifacts of the pandemic. Signs indicate shops are closed and emergency orders are in effect.

Human voices are hardly audible. Sirens overpower a child on a squeaky swing. People bang on pots outside their windows to recognize the work of doctors and nurses.

This video evokes memories of occupation, passed down by generations who lived through Italy’s fascist era. In one shot, an Italian flag is draped from an open window. People distanced by two meters queue outside a store, evoking food shortages during the war. A child’s chalk drawing of a cloud and sun on the pavement momentarily seems to resemble the coronavirus infecting a human cell.

A well-designed poster taped to a window explains social-distancing protocols. Another offers a handwritten slogan that assures passersby that “tutto andrà bene” (everything will be okay). The slogan is replicated as a hashtag with rainbows drawn or painted by hand across the city.

Discarded plastic gloves appear, relics of the pandemic, yet moments of hope emerge. A young couple kisses. The camera lingers on a billboard for exhibition space with a cute charcoal cat. The camera frames and reframes the gargantuan “torta nuziale” (wedding cake) building, a monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, who united Italy in 1861.

The short video serves as a poignant reminder that Europe was as vulnerable to COVID-19 as China and Iran, with Italy as the first Western epicenter.

Published on The New Yorker’s YouTube channel, the video is one of a series of city portraits of Atlanta, Milan, New Orleans, New York, Paris, Seoul, and Tehran.

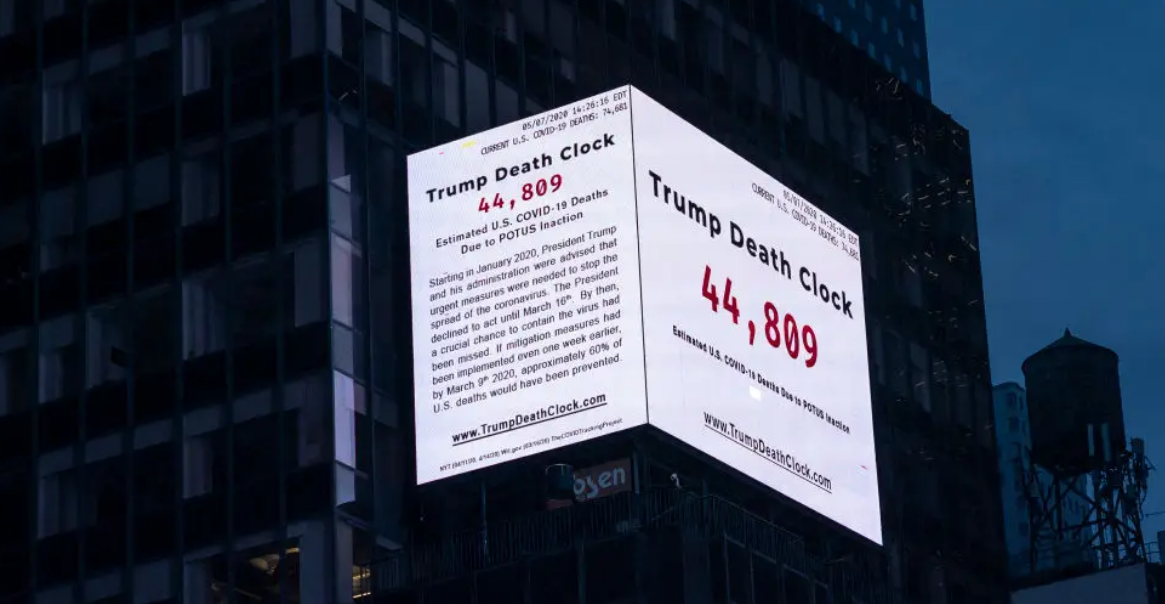

Trump Death Clock (Eugene Jarecki, United States, 2020)

Exhibited on a 17-meter electronic billboards above Times Square in the sitting US president’s former home of New York City and also available online, the Trump Death Clock aggregates data from The COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic (United States, 2020–present, Zach Lipton, Josh Ellington, and Ken Riley) as a response to what many consider gross negligence and incompetence on the part of the Trump administration.

Like other democracies that have been shaken in recent years by ethno-nationalist populism, the United States suffers a disproportionately large number of coronavirus cases and deaths for so-called developed countries. For a reality-television-star-cum-politician, numerical data is equivalent to audience shares and retweets, that is, they are more “real” than the deaths of citizens.

What this project achieves is interpreting numerical data to make the number of deaths due to political inaction by the Trump administration legible. Filmmaker Eugene Jarecki was inspired by the US Debt Clock (United States, 1989, Seymour Durst), which tracks national and each family’s responsibility on billboards installed at different locations in Manhattan over the years.

Two Weeks as a New York City Nurse in the Pandemic (The Intercept, United States, 2020)

This piece chronicles the work and home life of Maia Kwon Ferre, a nurse in New York City with a three-month-old baby. Toggling between the vertical formatting of talking to her mobile and the horizontal format of talking to her computer, she reflects on the vast changes to hospitals in the three months of her maternity leave. She describes the lack of personal protection equipment (PPE) in New York City hospitals where 30–40% of the nursing staff has been out sick.

She explains that most of the nurses in New York City are immigrant women of color. Shots inside the hospitals where she is deployed show wards that are so changed by the pandemic that they are almost unrecognizable. She explains that nurses are wearing a N95 mask, covered by a surgical mask, and then covered by a face shield. She shows a box of masks that were shipped to a friend from his mother in Hong Kong. The video also shows the socially-distanced protests of nurses, who advocate for more PPE and the nationalization of these industries.

The video was produced by The Intercept, an independent news organization known for its uncompromising adversarial journalism and in-depth investigations of war, surveillance, corruption, the environment, criminal justice, corruption, and injustice. Pierre Omidyar, founder of eBay, provided funding to initiate The Intercept, and continues support through First Look Media Works.

***

Dale Hudson is an associate professor of Film and New Media at New York University Abu Dhabi and digital curator for the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival (FLEFF). He is author of Vampires, Race, and Transnational Hollywoods (2017) and co-author of Thinking through Digital Media: Transnational Environments and Locative Places (2015 with Patricia R. Zimmermann). His essays appear in Afterimage, American Quarterly, Cinema Journal, Jadaliyya, Media and Environment, Screen, Studies in Documentary Film, Studies in South Asian Film and Media, and elsewhere.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is professor of Screen Studies at Ithaca College and codirector of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival (FLEFF). Her most recent books include Thinking Through Digital Media: Transnational Environments and Locative Places (with Dale Hudson,2015), Open Spaces: Openings, Closings, and Thresholds of Independent Public Media (2016), The Flaherty: Decades in the Cause of Independent Film (with Scott MacDonald,2017), Open Space New Media Documentary: A Toolkit for Theory and Practice (with Helen De Michiel, 2018), and Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics (2019).