Queer Cinema from Mainland China

When I started to create a playlist on Chinese queer cinema, I was immediately confronted with some big questions: What is Chinese? What is queer? What is cinema? … These are all complex questions open to much debate in academia. If we cannot answer these questions, is it still possible to put together a playlist, or should we give up the effort all together? Even if we have managed to assemble a playlist, is the list representative or good enough? What titles and filmmakers do we include and exclude? Is a ‘representative’ playlist ever possible?

On the other hand, there are evidently films made by, for, and/or about LGBTQ people from China and the Sinophone sphere. There are clearly people who want to watch them and who like them (and I am one of them). So I ventured to embark on such an impossible task, focusing on the films that I have seen and liked – at the same time aware of the huge limitation of my own experience and preference.

My playlist therefore focuses on films that centre on queer people’s lives, or films in which queer people’s stories are central to the film narrative, regardless of the gender and sexual identities of the filmmakers and the target audience. These films were largely produced and circulated in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), or mainland China. I am aware of the exclusion of films from the Sinophone sphere as well as the selectivity of such a list, and I hope that readers can expand the list.

The film titles are arranged in a chronological order. Interested readers can find more titles, filmmakers, and critical discussions in the following books: Celluloid Comrades: Representations of Male Homosexuality in Contemporary Chinese Cinemas (Song Hwee Lim, University of Hawai’i Press, 2006), Backward Glances: Contemporary Chinese Cultures and the Female Homoerotic Imaginary (Fran Martin, Duke University Press, 2010), Independent Chinese Documentary: From the Studio to the Street (Luke Robinson, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), New Queer Sinophone Cinema: Local Histories, Transnational Connections (Zoran Lee Pecic, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), Queer China: Lesbian and Gay Literature and Visual Culture under Postsocialism (Hongwei Bao, Routledge, 2020), and Queer Representations in Chinese-Language Film and the Cultural Landscape (Shi-Yan Chao, Amsterdam University Press, 2020), among others.

Major queer film festivals in mainland China include: Beijing Love Queer Cinema Week (formerly Beijing Queer Film Festival, since 2001), ShanghaiPRIDE Film Festival (since 2012), and Shanghai Queer Film Festival (since 2016). An important archive for Chinese independent cinema (including queer cinema) is Chinese Independent Film Archive (CIFA, since 2020). Some of the films on this playlist have been discussed in my column Lao Bao’s Queer Lens on the CIFA website: https://www.chinaindiefilm.org/publications/special-columns/bao-hongwei-2/

Farewell, My Concubine (霸王别姬dir. Chen Kaige, 1993)

Classical Chinese theatre has a long tradition in crossdressing performance and homoerotism. With the founding of the PRC, both crossdressing and homoeroticism were classified as ‘feudal remnants’ incompatible with the communist governmentality and had to be eradicated from society. In this melodramatic film, two male opera singers’ love entanglement unfolds against the backdrop of the twentieth-century modern Chinese history. A beautiful film that features the virtuoso performance of the Hong Kong queer icon Leslie Cheung.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fF-AspF17AQ

East Palace, West Palace (东宫西宫dir. Zhang Yuan, 1996)

Scripted by Chinese writer Wang Xiaobo and turned into a film by China’s Sixth Generation filmmaker Zhang Yuan. An overnight interrogation of a cruising gay man at a police station located in a park leads to the man’s unstoppable confession of homosexual desires. The seductive power of queer confession subverts the patriarchal and heteronormative state power represented by the policeman. This was the first film in post-Mao China that explicitly featured a gay man who unabashedly confesses his queer love and desire on screen.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q0moLmZKiKs&list=PLtYlXmlwFcqkf-uUSw0fE2Z6S_M8pWwub

Miss Jin Xing (金星小姐dir. Zhang Yuan, 2000)

The first documentary film about trans people in post-Mao China. Zhang Yuan’s film focuses on the life of China’s trans celebrity Jin Xing before and after her transitioning. In this film, Jin Xing is represented as an enigmatic figure leading an unusual life and possessing a captivating power in telling stories. If her stories sound fascinating and even enchanting, this is because they were told by a legendary figure. Jin Xing’s life becomes the biggest legend in the film.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LRCttWH8hc0

Fish and Elephant (今年夏天dir. Li Yu, 2001)

The first lesbian-themed fiction film in post-Mao China. The film reveals the relationship between two working-class women, showcasing the difficult lives that Chinese lesbians lived in the 1980s and 90s. As filmmaker Li Yu’s feature debut, Fish and Elephant can be seen both as a feminist film and a queer film. Shot underground on a 16 mm format, Fish and Elephant is a quiet, slow, but beautiful film. The film cast consisted entirely of non-professional actors and actresses, one of whom was Shi Tou, who later became a queer filmmaker and activist herself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wM9bxWpy82o

Shanghai Panic (我们害怕dir. Andrew Yusu Chen, 2001)

Based on Mian Mian’s novel We Are Panic and directed by Andrew Yusu Chen, the film follows the lives of four young people in their twenties from Shanghai. They have sex, take drugs, and deal with self-inflicted traumas; they do not seem to have jobs or big ambitions and they belong to a lost generation in China’s post-Mao era. The film was shot on digital video and in an experimental style.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kAJszk41wE4

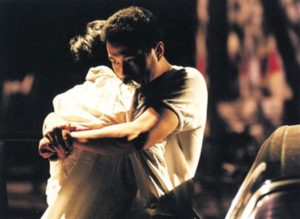

Lan Yu (蓝宇dir. Stanley Kwan, 2001)

Adapted from an online queer novel Beijing Story, Stanley Kwan’s film Lan Yu remains one of the best known Chinese queer films. The film feature two gay men’s romantic but tragic love story over a period of ten years, punctuated by their traumatic experience at Tiananmen in 1989. When historical trauma and personal trauma overlap, a story of ‘becoming gay’ becomes a national allegory for post-Mao China. The film’s production and circulation also open up discussions about queer Sinophone politics.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1aHTVL8583w

Queer Comrades (同志亦凡人dir. Queer Comrades, 2007-)

Celebrated as the longest running queer webcast from the PRC, Queer Comrades is also a community media organisation and online streaming platform. The programme documents different aspects of queer community life in the formative years of queer urban identities, communities, and activism in China. The short documentary videos that Queer Comrades produced offer a rich queer community video archive in the PRC in the first two decades of the twenty-first century.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCxsgHqUyuERElUOqY9duGMg

Queer China, ‘Comrade’ China (誌同志dir. Cui Zi’en, 2008)

A documentary about the queer community history in the PRC from the 1980s to the 2000s, made by the celebrated Chinese queer filmmaker Cui Zi’en. The film uses a chapter structure (as in a history book) to document developments in LGBTQ rights, literature and arts, community, and activism in the post-Mao period. The film features many interviews and reuses historical footages; it is an important historical record.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PBRE7UtSyn0

Spring Fever (春风沉醉的夜晚dir. Lou Ye, 2009)

In this nearly two-hour long and emotionally intense fiction film about a complex love pentangle, China’s Sixth Generation filmmaker Lou Ye exploits the topic of homosexuality for an international audience (as the film was and still is banned in China). The film introduces the figure of a tongqi, or wife of a gay man, symptomatic of the queer existence in China at the time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U0DTUErg9-A

The Lucky One (宠儿dir. He Xiaopei, 2012)

Queer filmmaker He Xiaopei’s debut documentary about a woman dying of HIV/AIDS. The filmmaker gave the protagonist a video camera and a digital audio recorder and asked the protagonist to document the last days of her life. The end of the story turns out to be out of everyone’s expectation. Is it fiction, or is it reality? Where does life end and documentary start? For the filmmaker, the dying woman exercised her full agency through digital storytelling.

https://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XMzQ0OTUwNjIw.html

Mama Rainbow (彩虹伴我心dir. Fan Popo, 2012)

Best known for the legal disputes surrounding the film – queer filmmaker Fan Popo took China’s media censor, the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, to court for the latter’s censorship of his film Mama Rainbow in 2015. But the film itself is worth watching – it was made in an activist and collaborative approach by working closely with the community, and it tapped into the important topic of queer parent-children relationships. Together with Fan’s other two films (Chinese Closet and Papa Rainbow) which make up the ‘Chinese queer family trilogy’, this film serves as a good example of the queer community documentary from the PRC.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jFaKcCQCxKE

We Are Here (我们在这里dir. Sam Jing Zhao and Shi Tou, 2015)

A documentary film made to mark the twentieth anniversary of the Fourth United Nations World Conference for Women. It also offers a historical account of Beijing’s lesbian history since 1995. The film raises interesting questions about the relationship between China’s queer history and women’s history, and about the place of Chinese feminism and the queer movement in an international context. An important record of queer history.

http://dixonplace.org/performances/we-are-here-film-screening/

Extravaganza (炫目上海滩dir. Matthew Baren, 2018)

Shot from the backstage of a drag performance inside a Shanghai theatre, this documentary follows a group of drag kings and queens getting themselves ready for the start of the show. Paying homage to Paris is Burning(dir. Jennie Livingstone, 1990), British filmmaker Matthew Baren’s documentary Extravaganza gives a rare glimpse into a small, cosmopolitan, and dynamic drag subculture in Shanghai. The film also broadens the definition and purview of Chinese queer cinema.

Shanghai Queer (上海酷儿dir. Chen Xiangqi, 2019)

A documentary about Shanghai’s queer history from 2003 to 2019, featuring interviews with queer activists, artists, filmmakers, scholars, and ordinary people living in Shanghai. The film was made in a collaborative and participatory approach. The filmmaker’s subjectivity is clearly manifested in the film through voiceovers and intertitles. An important historical record.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tjta-Nd3POY

A Dog Barking at the Moon (再见南屏晚钟dir. Xiang Zi, 2019)

Xiang Zi’s feature debut is a family drama that follows her real, thorny family life, centring on estranged parents living in a toxic marriage. The father is discovered to be gay and this seems to be at the root of all troubles, while the mother takes to a cult religion and indulges in a blame game. The incorporation of stage performance – inspired by the classical Chinese theatre convention – in the film is impressive.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PRsCQaXn4_o

***

Dr Hongwei Bao is an associate professor in media studies at the University of Nottingham, UK, where he also directs the Centre for Contemporary East Asian Cultural Studies. His research primarily focuses on queer cultures in contemporary China, including queer films, literature, art, and performance. He is the author of Queer Comrades: Gay Identity and Tongzhi Activism in Postsocialist China (NIAS Press, 2018) and Queer China: Lesbian and Gay Literature and Visual Culture under Postsocialism (Routledge, 2020).