NOTE: As a piece designated ‘Thinking Aloud’, I recommend reading it as that.

On Tuesday, 29 October 2019, U.S. Representative Ilhan Omar (D-Minnesota) abstained from voting on a mesaure to have te US officially recognise the Armenian Genocide. She did not vote against this measure (the 11 nays are solely attributable to the Republican Party), but her abstention has made the news, possibly for its seeming conflict with her activist stance embedded in recognising the struggles and pain of others.

To be fair, I understand her questions. I have no doubt about the occurence of the Armenian genocide and I believe it was a genocide. I also support the need for recognition in the face of years of denial and the suffering this has caused survivors and their families. Any yet, I did ask ‘why now’? This resolution has been on the table for decades, and it cannot come as a complete surprise that it arises and was able to pass as diplomatic relations are at a low, including sanctions too, having been levied. I am not so innocent as to think that it was only a well meaning intention to survivors of human rights abuses that occasioned this vote. As such, Rep Omar’s concern about this vote as ‘political cudgel’ has resonance, although I don’t know if I would necessarily make that a criterion, especially given that recognition, remembrance, and representation are always political.

As she asks for ‘academic consensus’– another concerning phrase as I will get to– I come in, not as a scholar of genocide, but a scholar of how film and other screen media have been used to bear witness to genocide and how to mobilise audiences to action to respond to her actions and concerns.

Whilst due in part to the absence of official recognition, the present day understanding of the Armenian genocide as forgotten overlooks how widely reported the crisis was at the time. From the Hamidian massacres (1894-1896) to the genocide of 1915 to the conditions of privation, homelessness, and expulsion that continued into the 1920s, the atrocities that were part of building a pan-Turkic state were part of a media landscape. Articles in newspapers and magazines, photographs, diplomat letters and reports– including those of then-Ambassador Henry Morgenthau– survivor testimonies, posters, political cartoons and a joint declaration from the US, Britain, and France, called what was happening ‘Crimes Against Humanity’-– These all covered the atrocities and the urgent need to act.

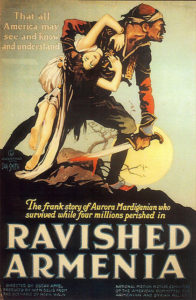

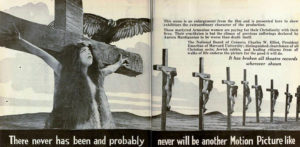

The film, Ravished Armenia (1919), based on the testimony of survivor Aurora Mardiganian, featured that survivor as herself and offered a cameo by Ambassador Morgenthau. A proto-Hollywood film (a Selig Polyscope production), it was co-produced by Near East Relief and made part of a multi-media $30 million fundraising campaign. The screenings (often coming with the impressive ticket prices of $2.50-$10 where 25cents was more typical) were orchestrated as events designed to enhance both experience and awareness building. Screenings were held in conjunction with luncheons, plays, and guest speakers—typically diplomats, relief workers and survivors. These speakers corroborated the truth of the depiction and further animating it with their own testimony and presence. This was perhaps made most extreme in the case of Aurora, who toured with the film (until exhaustion claimed her and Aurora impersonators were hired).

Of course, as well meaning and urgent as this was, we cannot overlook the other politics embedded in this rescue mission. Not surprisingly, especially given the Protestant evangelical roots of NER and the biblical associations with Armenia (e.g. Ararat), the Christian identity of the victims was emphasised. Ravished Armenia features a spectacular sequence depicting the mass crucifixion of naked women— bringing in the popularlity of Orientalist popular culture that delighted in the titillations of sexual violence and harems. And as no surprise, then, the Turkish people were filtered through dehumanising tropes that highlighted their Muslim identity (ironic in light of the largely secular dimension of the Turkish state-building enterprise of which this genocide was part).

Such imagery worked to engage audiences through the use of familiar frames—those that stimulated sympathy, outrage and interest. Filtered through recognizable tropes, the suffering became one of moral outrage and horror visited upon innocent Christians by barbaric Easterners and Muslims.

I share this not to condemn these projects, nor to create an argument against recognition of an event, or series of events, that has caused so much pain, but to acknowledge the politics that are an inevitable component of recognition and representation.

Such politics are hardly one way. Indeed, despite the great attention to this genocide and its attendant horrors, the U.S. did not make this a cause for international justice (as would happen following the next genocide with the International Military Tribunals of the Nuremberg Trials). Geopolitics factored in, to be sure, as did battles that played out in the cultural landscape.It is not just the Armenians (or others) who may have constituted a threat to the mythology of the Turkish national project, but also the very memory of the Armenian genocide.

As such, multiple erasures of all things Armenian, including the genocide, have become part of the monoloithic nationalism (again, ironic given the extraordinary cosmopolitanism of Istanbul) in what Anush Hovanissian has described a ‘cultural genocide’. Physical objects and monuments are part of this action; and so too has film been a charged battleground for memory. When The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, Franz Werfel’s popular novel of Armenian resistance during the massacres, was optioned by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1934, the Turkish Ambassador, Münir Ertegün Bey, informed the US State Department that the production of this film could have unfortunate repercussions on diplomatic relations with Turkey. As the State Department brought pressure upon the Hays Office to quash the film, letter writing and print media campaigns launched by the Turkish Embassy threatened an international boycott not only of all MGM films, but of American films altogether. Production on the film ceased immediately.

In 2000, it was reported that there had been pressure as the Turkish government threatened Microsoft with ‘serious reprisals’ unless all mentions of the Armenian genocide were removed from the Microsoft Encarta entries on ‘Armenia’ and ‘Genocide’. In turn, Microsoft allegedly demanded its authors edit the entries.

And in 2006, multiple PBS affiliates were pressured to air a discussion programme, ‘Armenian Genocide: Exploring the Issues’ following its broadcast of a documentary about the Armenian genocide (The Armenian Genocide). This programme featured a panel of four academic ‘experts’ to discuss the genocide, or more problematically, whether it was a genocide. This included Taner Akçam, a human-rights defender and historian of the production of Turkish national identity and Peter Balakian, author of The Burning Tigris as well as two well-known Armenian genocide deniers. In effect, following a screening of a film that recognised the genocide as genocide, the stations opted to open the genocide to debate for ‘academic consensus’.

It is hardly any surprise then that Rep Omar’s call for ‘academic consensus’ resulted in so much anxiety, given its coded use in genocide denial. Nor is it any surprise that given the history of Turkish involvement in these overseas cultural and political determinations, that people would begin to look for evidence of influence on the Representative, for instance, through donations. At a time when a crucial recognition of a persistently denied genocide has taken place, her actions resonate with the past history of attempted erasures.

There are so many other thoughts I have on the matter, and am keen to invite conversation. However, as I also know that the topics of Rep. Omar, the Armenian Genocide, and Israel (which is likely to be dragged in) are hot issues that can result in invective this blog cannot host, I will monitor the comments carefully, and shut them down if the conversation cannot stay productive.

References/ Further Reading:

Peter Balakian, The Burning Tigris (Harper Collins, 2003).

Edward Minasian, ‘The Forty Days of Musa Dagh: The Film That Was Denied’ in Journal of Armenian Studies 3.1-2 (1986-7).

Suzanne E. Moranian, ‘The Armenian Genocide and American Missionary Relief Efforts‘ in Jay Winter, ed. America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915 (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Anthony Slide, Ravished Armenia and the Story of Aurora Mardiganian (Scarecrow Press, 1997)

Leshu Torchin, ‘Since We Forgot: Remembrance and Recognition of the Armenian Genocide in Virtual Archives’ in Frances Guerin and Roger Hallas, The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory, and Visual Culture (Wallflower Press, 2007).

Leshu Torchin, ‘Ravished Armenia: Visual Media, Humanitarian Advocacy, and the Formation of Witnessing Publics‘ in American Anthropologist 108 (2008).

Leshu Torchin, Creating the Witness: Documenting Genocide on Film, Video, and the Internet (University of Minnesota Press, 2012).